This

post is about the history of the Milton Camp, sometimes called

Lavinia's Camp Ground, Lavinia's Grove camp, or Lavinia's Wood camp.

Because of the camp's long history and many areas of interest, I am

dividing the article into two segments. Part I will look at the history

of the camp and the social drivers behind it, and Part II will present

some first-hand accounts of camp meetings.

With

a few interruptions, the Milton camp meeting - an outdoor "tent

revival" in August that ran a week or more in Lavinia's Woods - lasted

at least until 1965. There is nothing I can find in the Delaware

newspapers after 1965 to indicate either that the camp meeting continued

to take place, or when it was abandoned. There were actually two camp

meetings every year at Lavinia's Woods - one attended by African

Americans under the auspices of the local A. M. E. congregation, and one

by the Milton Methodist Protestant Church attended by whites. The color

line was not a solid barrier, as some members of both races attended

each other's camp meetings from time to time. However, for lack of

sufficient resources at my disposal, this post is limited to the white

people's camp meeting.

Before

I delve into what is known about the camp meetings, some historical

background is necessary to explain this enduring feature of American

Protestant religious life.

The Great Awakenings

In

the context of religion, the term "Awakening" refers to the end of a

long slumber of secularism and religious indifference. Theological

historians have defined three periods in the 18th and 19th centuries

when evangelism acquired renewed momentum and many new converts were

brought into the Methodist and Baptist traditions. The First Great Awakening

began in England in the 1730's and lasted until 1743 after being

exported to the American colonies. This first revival was powered by a

new style of sermonizing that eschewed the dense theological

investigative sermons that ministers read to the congregation, in favor

of a style of communication, often extemporaneous, that sought to

spiritually energize the audience and attract converts.

The Second Great Awakening

began in the United States in the late 18th century and reached its

peak in the middle of the 19th. The so-called "fire and brimstone" style

of preaching is one example of a new type of theological rhetoric that

was not directed at the intellectual elites of society, but rather to

the common, less-educated population. It was evidently quite successful.

One area of western New York State (bordered by Lakes Erie and Ontario

to the north and west, and including much of the Finger Lakes region)

was dubbed the "burned-over district" because the sheer number of

converts there meant no more "fuel" (potential new converts) to "burn"

(convert). The temperance, women's suffrage, and abolitionist movements

of the 19th century had deep roots in the reformist spirit that was part

of the religious fervor of the "burned-over district." The area also

spawned Mormonism and several utopian movements.

Western

New York State was an underpopulated frontier area in the early 19th

century, as were Kentucky, Ohio, and Tennessee. It is in this period

that camp meetings led by preachers of various Protestant denominations

began to spring up. Presbyterian minister James McGready is generally

thought by historians to have originated the first camp meeting in the

U. S., in Kentucky, in 1799 - 1801. These camp meetings were described

as highly emotional, and participants were susceptible to states of high

excitement, rapture, "convulsions," speaking in tongues, and the like.

Attendees literally camped at the meeting, as there were no hotel

accommodations to be had in frontier areas.

The

sustained excitement stoked by preacher after preacher for hours and

days on end, and the congregation of thousands of normally isolated

people at these first camp meetings bred all kinds of non-spiritual

excesses, including drinking, gambling, and (according to at least one

observer) sexual promiscuity and abandon. A common joke at the time

maintained that frontier populations spiked about nine months after a

camp meeting, and the newborns were called "camp meeting babies." There

is no way to verify the truth of this assertion, facetious or not.

By

the 1850's, camp meeting organizers maintained increased vigilance over

attendees' behavior and the excesses of the earlier years were kept

under better control. By the time of the Third Great Awakening

in the latter half of the 19th century, Methodist churches in the

mid-Atlantic region, including Delaware, operated perennial camp

meetings in the summer months in many locations; evangelism advanced on

multiple fronts, including missionary work, permanent religious retreats

at Rehoboth, DE and Ocean Grove, NJ, and the Y. M. C. A.

The Milton Camp Meeting (Lavinia's Camp Ground)

The

Milton Camp Meeting at Lavinia's Camp Ground just outside of town, to

the best of my knowledge, has its origins in the Third Great Awakening.

The earliest newspaper reference to it can be found in the September 6,

1873 issue of the Wilmington News Journal, but I believe this

camp meeting, run by the Milton Methodist Protestant Church, would have

begun some years before that. A report in the August 3, 1914 issue of

the Wilmington Morning Journal asserted that Lavinia's Camp was

about sixty-six years old, which would bring its initial year to 1848,

several years before the establishment of the Milton M. P. congregation

in 1857. Yet another newspaper article suggests that the camp may have

been started by the Methodist Episcopal Church as early as 1835.

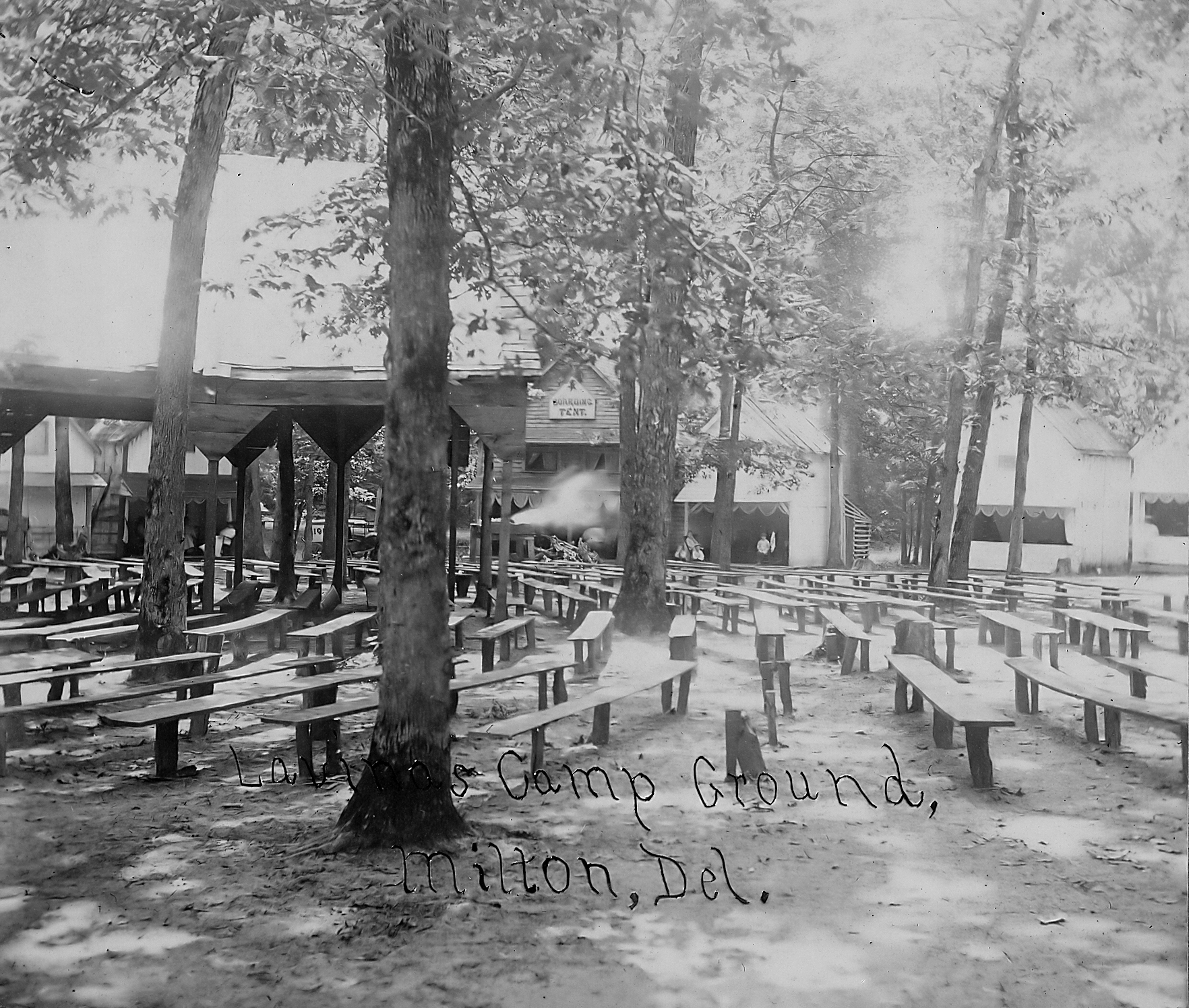

Lavina's Camp Ground, ca. 1911, photographed by Dr. William H. Douglas (Milton Historical Society collection)

The

photograph above, found in the Douglas Family folder, is one of only

two known photographs of the Milton Camp Meeting. In the background are

the "tents," which were actually small cottages owned or rented by

families attending the camp meeting. They are two stories tall,

presumably with the bedroom(s) in the upper floor and an open sitting

area on the ground floor. Some have ornamentation (the balconies and

railings in the two leftmost cottages). These cottages were arranged in a

circle around the tabernacle, which is not visible in the photograph

but would have been just beyond the benches in the right side of the

photograph. The benches themselves are arrayed in a semi-circle in front

of the tabernacle.

The

table-like structure in the right foreground with the wood pile next to

it was the source of light for nighttime activities: four logs with a

dirt-filled slab on top of them. A bonfire was built and lit at dusk on

top of the dirt.

Milton Camp Meeting, ca. 1911 photographed by Dr. William H. Douglas (Milton Historical Society collection)

The

photograph above, taken by the same photographer, appears to have been

taken on the opposite side of the camp pictured in the first photograph.

The evening fire on the raised dirt slab is smoldering at center

background. That and the low position of the sun through the trees

suggest that the photograph was taken in the morning. Some boys are

standing under the awning, to the right of the fire platform; an

automobile or truck is partially visible in the far background, to the

left of the smoke. The benches facing the tabernacle, at left, are

spartan; they have no backs and are just plain wood. Another interesting

feature is the "boarding tent" in the center background. Meals were

prepared, sold and served in the boarding tent, which was also a

permanent structure rather than canvas. The boarding tent as well as

several other services provided in the camp were operated by individuals

as "privileges" (concessions) that the Milton M. P. Church auctioned

off to the highest bidder. The following excerpt from the Milton News

letter in the Milford Chronicle of July 11, 1902 provides some insight

into the issues surrounding concessions at the camp meeting:

At

the sale of the privileges held on Saturday, the boarding tent brought

$1; the food pound $9; these were purchased by Prof. W. H. Welch. The

confectionery department was bought by John Barker for $5. One of the

officers of the church requests the writer to say that the small prices

these privileges were sold for was due to the action of the church,

which will not allow anything to be sold on Sunday; and the two Sundays

that include a part of the camp are the best days the proprietors of

these privileges can have. This may be all right from a moral

standpoint; but as these meetings are held more for sociality than for

spiritual comfort, you had better get all out of them that you can.

At

the sale of the privileges for the colored camp at Hazard’s Woods, near

the end of Milton Lane, the confectionery stand brought $36; and the

boarding tent $12. Witness the contrast, when viewed from a financial

standpoint.

The

"food" pound Conner referred to may have been the horse pound or

stabling area, as this was the age of the horse and buggy. Selling food

or confectionery at these camp meetings would not make anyone rich.

There was an additional problem: the Milton camp meeting was within easy

walking distance to the center of town, and attendees did not have to

rent a "tent" or buy food from the camp concessions if they chose not

to. Indeed, Milton town residents had always made up the bulk of the

attendance at the Milton Camp meeting, and could walk into or out of the

camp without difficulty.

There is also another statement in the first paragraph: ..these meetings are held more for sociality than for spiritual comfort.

By the early 20th century, the summer camp meeting was seen by many as a

social event, and there were few converts made. The value of the Milton

Camp meeting as an evangelical tool was called into question for years

by the M. P. church, but what led to the end of the church's involvement

with the camp meeting was something entirely different.

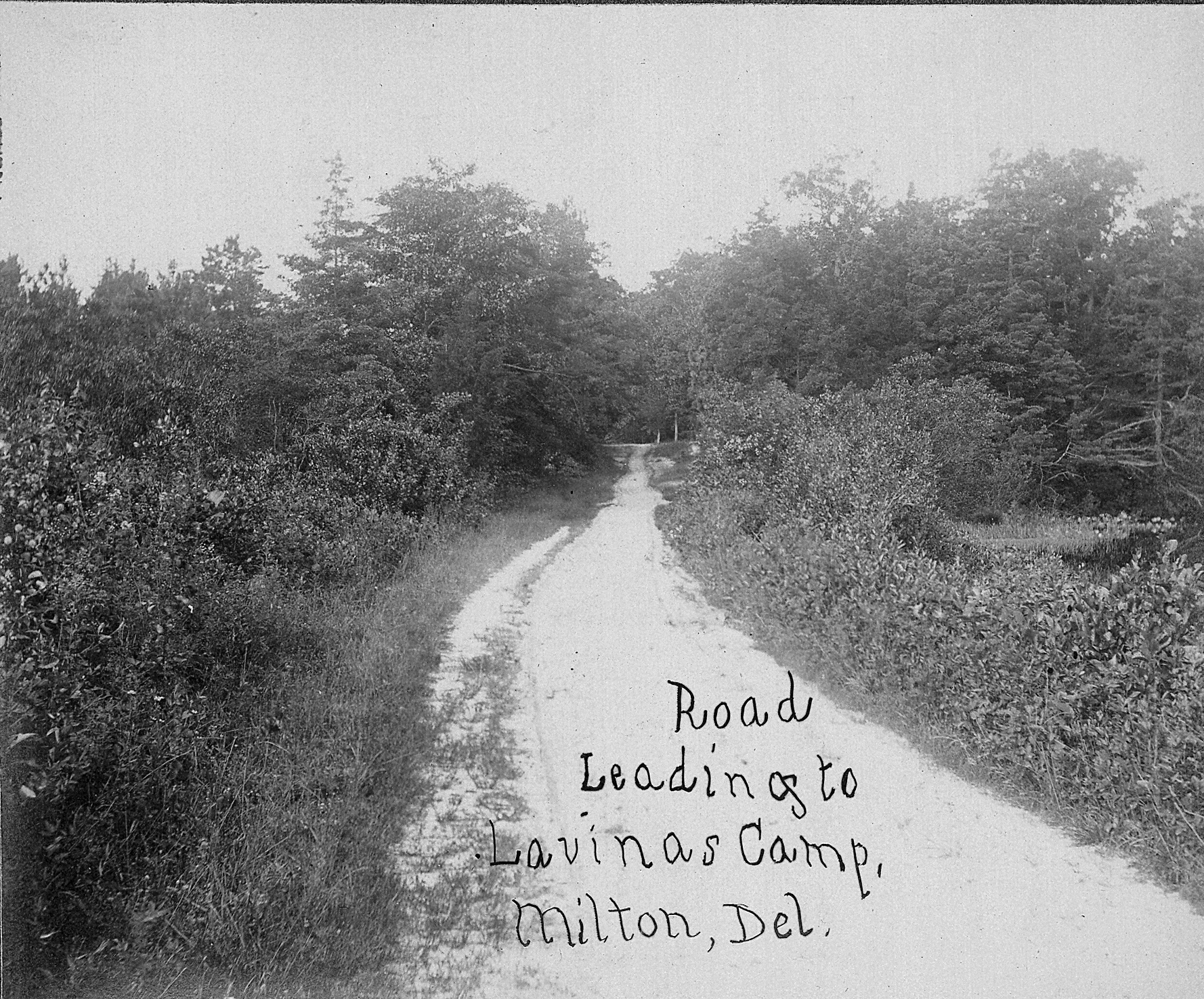

Road leading to Lavina's Woods camp, ca 1911 photographed by Dr. William H. Douglas (Milton Historical Society collection)

The End of the Milton Camp Meeting

In the July 22, 1918 issue, the Wilmington News Journal

reported several cases of what was first thought to be chickenpox in

one Georgetown family. The diagnosis changed to smallpox as the symptoms

became more severe, and a previously unreported outbreak of smallpox in

Gumboro came to light. Just two days later, the Wilmington Morning

Journal reported that camp meeting season was beginning to ramp up and a

full season was planned. But by July 30, organizers of several camp

meetings on the Peninsula, including the Milton Camp, were advised by

the State Board of Health not to hold planned meetings due to the fear

of contagion. The camp meeting did not take place that year, but the

decree to close it came after concessionaires and others had already

invested money in preparation.

In the August 4, 1919 issue of the Wilmington Morning News,

it was reported that the committee organizing that year's Milton Camp

meeting had decided not to hold it. The reasons given in that newspaper

were the lack of cooperation among members of the congregation and the

inability to find someone to manage the boarding tent. However, David A.

Conner, writing in his Milton News letter in the August 4, 1919 issue

of the Milford Chronicle, gave a somewhat different view of the

abandonment of the Milton camp meeting. He stated that it had for many

years been a social event rather than a spiritual one; before the advent

of the automobile and the railroad, the camp meeting was eagerly

anticipated by country people who were far from a church, were

relatively isolated, and needed a respite. Modern transportation had

provided all classes with the means to enjoy alternatives to the camp

meeting such as beach excursions, which were proving immensely popular.

A New Lease on Life

In

September of 1897, in Cincinnati, a group of Methodist Episcopalians

founded the International Holiness Union and Prayer League, which was

intended to be a fellowship and not a new denomination. By 1900,

however, the fellowship had acquired many adherents who were attracted

by its principles and its evangelic missionary work overseas. Its name

was changed to International Apostolic Holiness Union. By 1905, having

grown into a formal church organization in all but name, the group was

renamed to International Apostolic Holiness Union and Churches. After a

further period of growth and absorption of other religious bodies, the

overall organization adopted the name of one of the absorbed churches

and became the Pilgrim Holiness Church.

The

Pilgrim Holiness Church arrived in Milton in 1926, held their first

meeting on Easter Sunday of that year, and dedicated their church

building on April 11. This made a total of four Protestant churches

attended by whites of the town. In 1927, the newly established church

re-opened the Lavinia's Camp under their auspices. The camp continued in

operation until at least 1965.

Postscript

The

two Methodist branches, Episcopalian and Protestant, as the United

Methodist Church around 1940, with the result that the Milton Methodist

Protestant Church, or Grace Church as it had been renamed, became

superfluous to the administrative body of the UMC and disappeared by

1962. The former church building was restored in 2006 and is now the

home of the Milton Historical Society and the Lydia B. Cannon Museum.

On

June 26, 1968, The Pilgrim Holiness Church and The Wesleyan Methodist

Church of America were united to form The Wesleyan Church, which is

still a presence in the religious life of the Milton community.

Sources:

An Account of Lavina's Camp Meeting, anonymous typewritten manuscript (MHS Collection)

Wikipedia

Wilmington News Journal, September 6, 1873

Milton News letter, Milford Chronicle, July 11, 1902

Wilmington Morning Journal, August 3, 1914

Wilmington News Journal, July 22, 1918

Wilmington Morning News, August 4, 1919

Wilmington News Journal, July 3, 1959

Wilmington Morning News, July 10, 1965

No comments:

Post a Comment